WHOIS, Proxies and the GDPR – how consumers lost Security and Privacy

Artists Against 419 has to say this very clearly: There can be no consumer privacy and security while ICANN Registrars are the custodians of trust on the internet. ICANN has allowed a situation to develop that’s had the exact opposite effect of what the European privacy regulators aimed for, the protection of natural consumer privacy. In turn, this has further not only created a situation where consumers may be trivially deprived of privacy, but also security. Let’s look at this situation with quick examples.

Public safety must be treated as equally important to privacy rather than sacrificed. If privacy policies interfere with the investigators’ abilities to bring the perpetrators to justice, they create opportunities for cyber attackers to menace citizens, invade their privacy and abuse their identities. There must be a balance.

27 May 2019 – Dave Piscitello, Interisle Consulting Group, APWG Board of Directors

The European Union implemented the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), with the goal of protecting natural users’ private details, in May 2018.

ICANN and domain name registrars rose to this by taking the path of least resistance, redacting domain name registration details (WHOIS) from public view. This was despite the GDPR allowing personal details to be divulged under certain circumstances in the public interest. The GDPR also did not prohibit the publication of business registration details as there is a clear distinction between a natural and a legal person. The GDPR only applies to natural persons. Even currently, European registrars are still revealing European domain registrant details as highlighted by some folks at ICANN’s Stability, Security and Advisory Committee (SSAC):

The research report did not look at some of the most relevant and obvious examples, such as how and why natural and legal person data is collected and published in real estate registries, company registries, and trademark registries inside the EU; and how such registries outside the EU handle the data of subjects who reside in the EU. While the report stated that “most EU ccTLD operators continue to publish some (and sometimes all) contact data fields for domains registered by legal persons,”9 the report did not provide the details, such as a list of which ccTLDs publish what data.

https://www.icann.org/en/system/files/files/sac-112-en.pdf

Note: The scope of discussions here is to look at how criminal actors register a domain with the intent of weaponizing it to defraud consumers, how this plays off in a privacy environment, also what checks and balance of interests are available versus consumer safety. Compromised web content is outside this scope.

Whereas consumers could previously look up who a domain name belonged to and make an informed decision, they lost this ability. Already previously, many domain names were hidden behind proxies. The negative effect of proxies on the general consumer interest was already known as a study had been made of it by ICANN and published in the Results of the GNSO Whois Privacy/Proxy Abuse Study. Some salient points from this study:

- 46% of sampled advanced fee fraud cases used privacy/proxy-registered domain names;

- For domains used for illegal or harmful activities that were not registered using privacy/proxy services, very few calls to Whois-provided telephone numbers (derived from a list of those that appeared valid enough to call) were answered. Registrants of apparently lawful and harmless domains could not be reached 25-55% of the time, but the rate rose to 83-93% for domains engaged in harmful or illegal activity.

- Based on these findings, NPL was able to conclude that the hypothesis for the study is true, and that the percentage of domain names used to conduct illegal or harmful Internet activities that are registered via privacy or proxy services is significantly greater than those used for lawful online activities. They also found that the outcomes were consistent regardless of the method used to avoid providing viable contact information.

From this study, we can see criminals had been abusing privacy as a tool in their toolkit against consumers. This begs the question: Had ICANN just given criminals a free gift to abuse against consumers?

Effectively, this meant that consumers now had to rely on registrars to carefully vet their clients, the registrants, before allowing their services to be used and filter out garbage registration details. The GDPR has an accuracy requirement. Consumers lost the ability to do due diligence for themselves.

Yet to fully understand the implications of this on the general consumer, let’s first consider how criminals abuse domain names. In this scenario we’ll consider something Interpol alerted about last year, non-delivery fraud, which includes puppy scams. This threat type is vastly underestimated and ill understood. These criminals are regular abusers of the domain name system. They will register a domain name, use it at a hosting provider to host a website. However, they will hardly ever register the domain name using their real details. The details they supply may vary between credible looking details, although bogus, to totally garbage details.

In this scenario the criminal may use a registrar half way around the world in a different jurisdiction, then defraud a consumer in yet a third jurisdiction. Whereas you, the consumer, would be able to spot discrepancies easy, the registrar would not. In fact registrars typically do not check each and every domain name’s registration details. Only the most superficial checks are done, if at all.

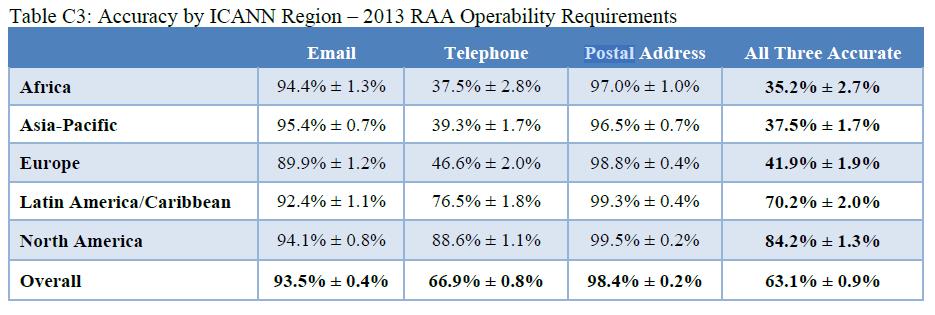

This is well known and ICANN would allow consumers to report inaccurate domain registration details. A study was also made of domain accuracy details regularly.

Not to take away from this attempt, it was effectively a measure of how good data looks. It had nothing to do with how traceable and accountable an abuser was if he were to abuse a domain to defraud somebody. We simply have to think of a pet scammer always being reachable until the point the consumer is defrauded, then stops responding. We also have to contemplate the claimed geographic distribution if the same party has different names and addresses in different countries at different registrars, sometimes even the same registrar. In effect, for a domain abuser, this study is a measure at how effectively he can lie or set up his infrastructure to defraud. Its common for the fraudsters we encounter to use VOIP phone numbers in the USA, GMail email addresses and a bogus US postal address. While the details may look good and pass automated or visual checks, the criminal is in Africa. We also notice that Africa has the lowest overall accuracy percentage at 35.2% in the above comparison.

While we can assume most domain users will never think of abusing a domain name to defraud consumers, our database bears testimony to certain miscreants doing exactly that and repeatedly so. Once such party has been doign so since at least 2007. More to the point, these few have a devastating effect on consumer rights and privacy, undermining the exact goals of the GDPR. We, also having some experience pre-GDPR with accuracy in addresses and ICANN Compliance staff self blinding, have lodged complaints on these issues, some still unresolved to date.

Yet its against this background that ICANN justified adopting the GDPR in WHOIS, allowing registrars to blank out registrant details. This rather misleading comment was reflected numerous times in the ICANN GDPR discussions:

In addition, some commentators have asserted that the accuracy principle of the GDPR requires registries and registrars to undertake additional steps to validate the accuracy of the data supplied by the registrant. The current Registrar Accreditation Agreement already includes accuracy requirements such as the validation and verification of some data elements, and the provision of notice to registrants about how to access, and if necessary rectify the data held about them.

https://www.icann.org/en/system/files/files/proposed-interim-model-gdpr-compliance-summary-description-28feb18-en.pdf

In reality the checks would be verify and email address, sometimes ringing a phone number. If the phone rings, the check is done in a tick-box exercise. This is also then how one oil company came to theoretically own a string of fraudulent websites with their address and telephone number. Even Intel was teh supposed owner of such websites. ICANN has made parties that had historically demonstrated themselves to be unreliable, to become the custodians of consumer trust on the net.

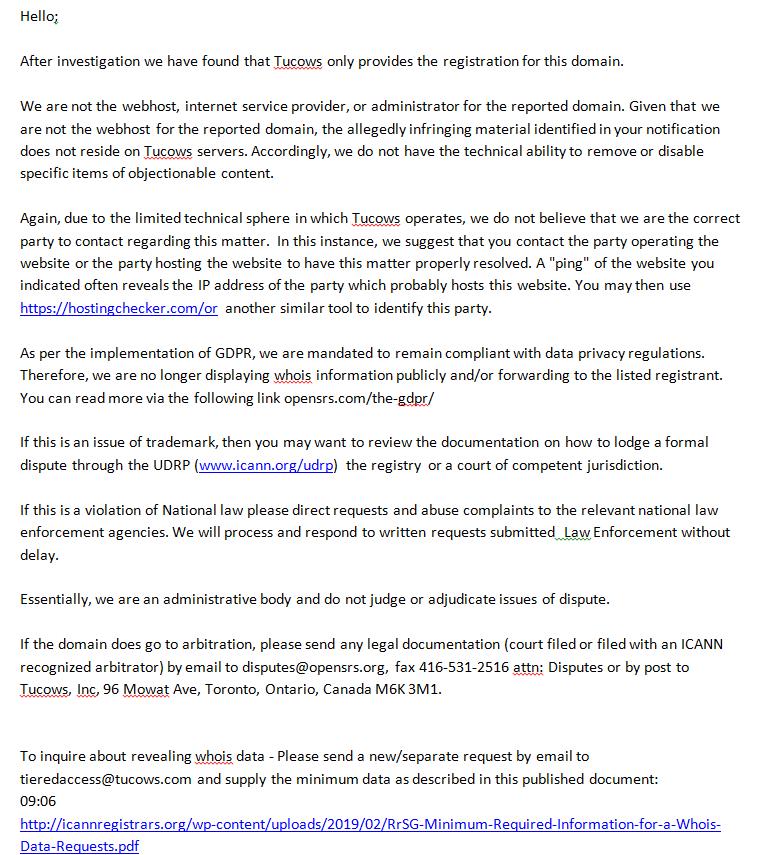

Yet, this is a role they disclaim. This group of parties has historically seem themselves to game even the most basic of policies. We can catch a glimpse of this in a response we had from one registrar, Tucows, even as the GDPR was implemented and used to hide patently bogus registration details they were made aware of.

Other countries have also implemented similar privacy regulations and their country code registries have also blanked out domain registration details. One such case is South Africa. South Africa is a hot-bed of cyber fraud where new fraud types tend to evolve from where it expands globally, yet it has no cyber crime statistics. South Africa was also the second highest ranking domain for fraud in 2020. As such its fit to look at how a similar complaint to the previous registrar played out where its name space was abused to facilitate fraud against its citizens.

A registrar in Germany, EPAG, was contacted to report patently fake domain registration details in the South Africa name space (.co.za). This happened just as the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) was being implemented by the South African registry operator, ZACR.

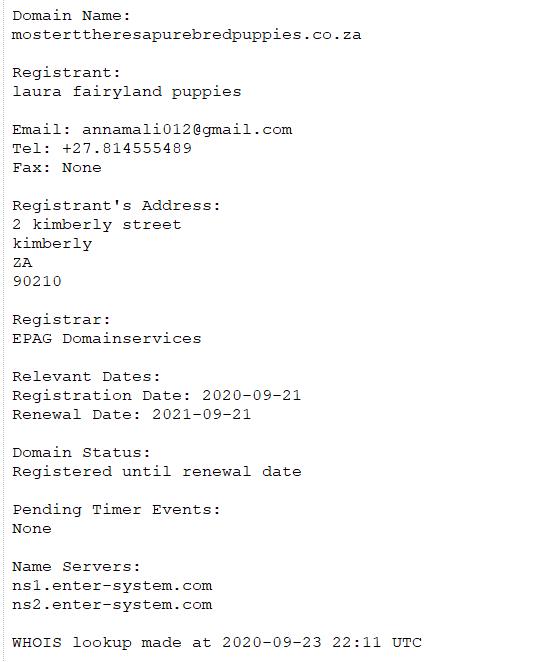

The party being reported to EPAG was using the same email and/or telephone number with ever changing names and addresses, also totally invalid postal codes. This party was then using these domains to defraud consumers, also steal their identity details and use these on the next set of victims. To get an idea of what was being reported, let’s consider mosterttheresapurebredpuppies.co.za, a pet scam.

Prior to POPIA being implemented, any user attempting to do due diligence and look at the domain owner, would have seen:

A quick check by a consumer would have shown that there is no Kimberly Street in Kimberly. More to the point, South Africa has four digit postal codes. The fraudster thought it funny using the Beverly Hills USA zip code as a postal code. South Africa’s ZACR also has a requirement that the Registrant Name be either the name of a real person or a registered business. “laura fairyland puppies” is not a registered business and its non-existence can easily be verified by a consumer at https://eservices.cipc.co.za/Search.aspx

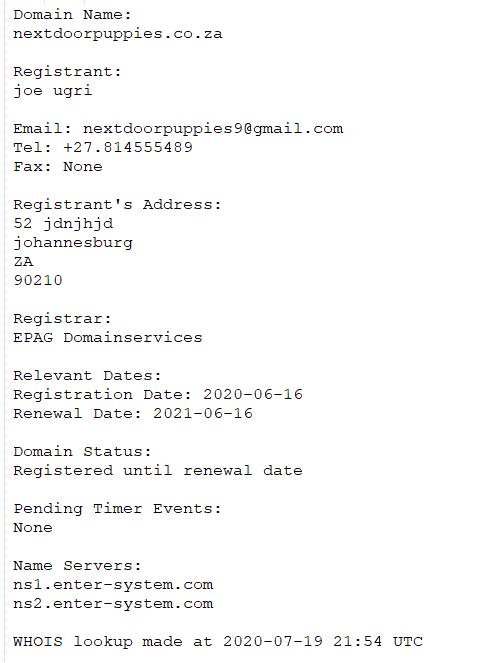

A slightly tech savvy consumer might have been able to find “laura fairyland puppies” was another pet scam. Perhaps a consumer would have come across nextdoorpuppies.co.za and looked up its registration details.

Obviously these two example registrations are the same party as can be seen by the telephone number. But in this case, even the most trusting consumer would have run a mile.

Yet, ironically, South Africa in its desire to protect its consumers, decided to implement POPIA mirroring the GDPR as an example. ZACR followed the example the ICANN community set, hiding domain registration details and making its registrars the guardians of trust. South Africans had been deprived of the ability to protect themselves by doing their own due diligence if they wished to purchase something from an unknown website.

As mentioned, these problematic registration details were reported to EPAG. Their response showed exactly what faith anybody can have in a domain they sponsor:

Essentially, despite being made aware of malicious domain registrations and these domains having fake registration details, EPAG distanced themselves from all responsibility. Yet they had the gall to abuse the GDPR as an excuse for now hiding patently fake domain registrations. The eagle eyed readers might have spotted the reply came from Tucows mentioned earlier; EPAG and Tucows are the same company. This is the exact same stance taken by Tucows on previously fake domain registration details where these domains are abused to perpetuate fraud, with also the GDPR being abused as an excuse.

For the record, the party mentioned here is having quite a spree defrauding consumers with anything from pets to containers. We have tagged this syndicate as DogGone in our database. This syndicate can be traced back seven years from their origins in the Cameroon and later migration to South Africa. While the registrar may feel its not their responsibility, we wonder what public will think when they learn that their pandemic of container scams, as reported on by CBC hitting unsuspecting Canadian consumers, are linked to this? Or indeed, what the Candian authorities will do when they realize their major registrar was used to give birth to the South African tender scam that is now also defrauding European and Canadian businesses? In their records they’ll even find UDRP D2017-1963 where they sponsored a domain for this criminal actor. Yet the registrar sees nothing wrong with allowing and facilitating fraud by abusing privacy laws to hide patently bogus domain registration details. To this registrar, these are mere puppy scammers, yet recklessly ignoring the alert from Interpol.

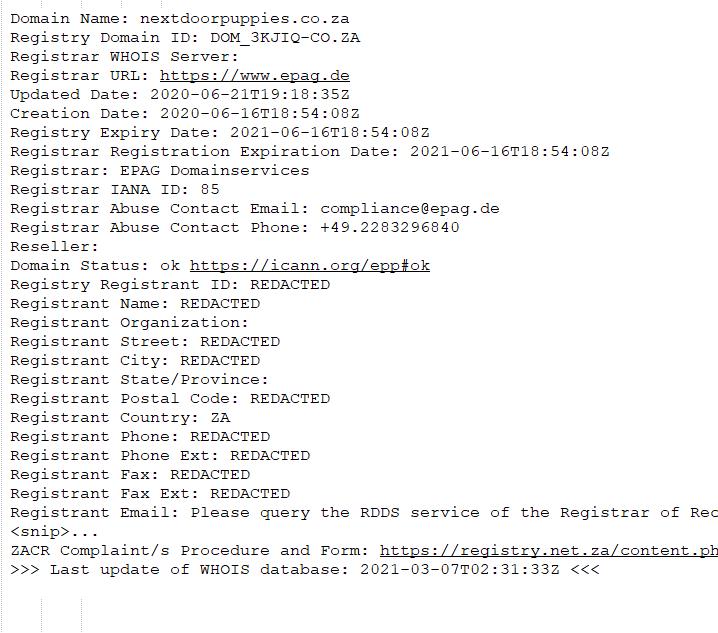

Any consumer attempting to do a query as to who has registered nextdoorpuppies.co.za today will see:

Consumers are now expected to sign a blank cheque and trust registrars when attempting to use the internet to purchase anything. This has led to many accounts of identity theft in South Africa. POPIA’s effects in domain registration details are following the exact same path as the GDPR’s perverse effect in domain registration details, with the same registrars facilitating it.

Another German registrar, 1API, also believes they are absolved from harm domains cause, kicking the can down the road. This was the response by them upon receiving evidence of domains under their sponsorship spoofing another party. This domain was being abused for fraud by a company specializing in non-delivery fraud facilitation from India as a business service :

The domain …(redacted).co.za…. is registered through our automated system by our reseller ……GoDaddy.com …..for their customer. We have forwarded your complaint to our reseller for further investigation.

Should your problem not be resolved to your satisfaction, please contact our reseller directly.

You may also contact the domain registrant, you can find his contact details by performing a whois query for the domain name.

We like to point out that we are merely the registrar of the domain name in question, and we neither control the concrete use of the domain name nor do we have access to any content hosted on this domain. Therefore we are not able to remove the content in question.

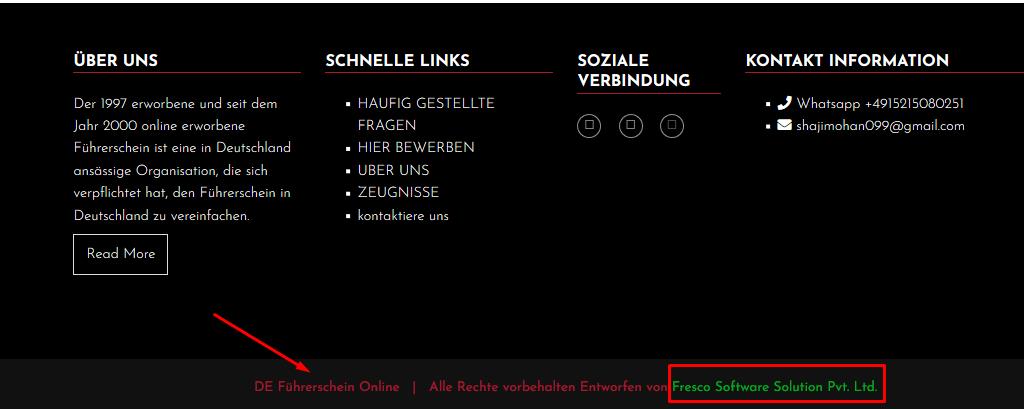

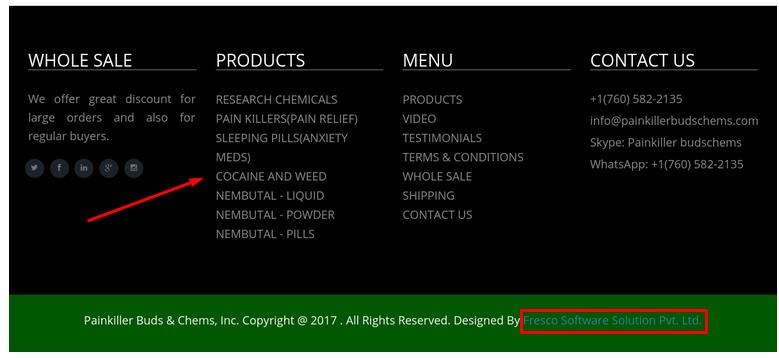

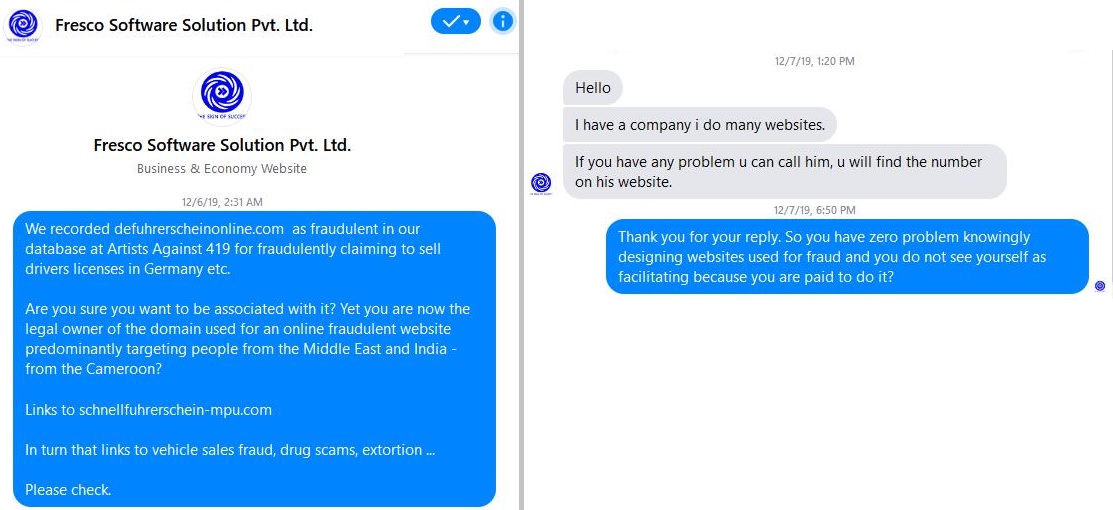

Since the topic of German registrars came up, the home of the GDPR, we need to perhaps have a look at what effect this is having on Europe. The last mentioned facilitating company is a good start. Forged driver’s licenses anyone?

The last slide shows the conversation with the facilitating company. So much for 1API’s suggestion in talking to the company facilitating non-delivery fraud, they just kicked the can down the road to anonymous criminals, something 1API did. This is just a small example of how businesses have zoomed in on the DNS space to facilitate fraud and is not uncommon.

Let’s stay on the topic of fraud affecting Germany. In one case the past week, a victim reported being defrauded by gloriapetshome.com. This domain is registered via Namecheap. This registrar implemented its GDPR version by offering its clients blanket proxy protection under its WHOIS proxy called WhoisGuard. In effect this means the registered owner becomes the proxy and the person using it the licensee. Namecheap is also the registrar of choice for all kinds of domain abusers, from spammers and phishers, to botnet herders and, as in our case, non-delivery and 419 scammers. Their extremely tolerant policies will be illustrated a bit later. This is the world’s second largest registrar.

To understand the pet scam and the illegality in its most basic form, a fraudster downloads an image of a pet he has no access to, then publishes this image as being a pet for sale. Obviously this is fraud and acknowledged as such globally. This modus operandi is also used by these syndicates for anything; from babies to drugs, from containers to much needed ventilators in the CovID pandemic.

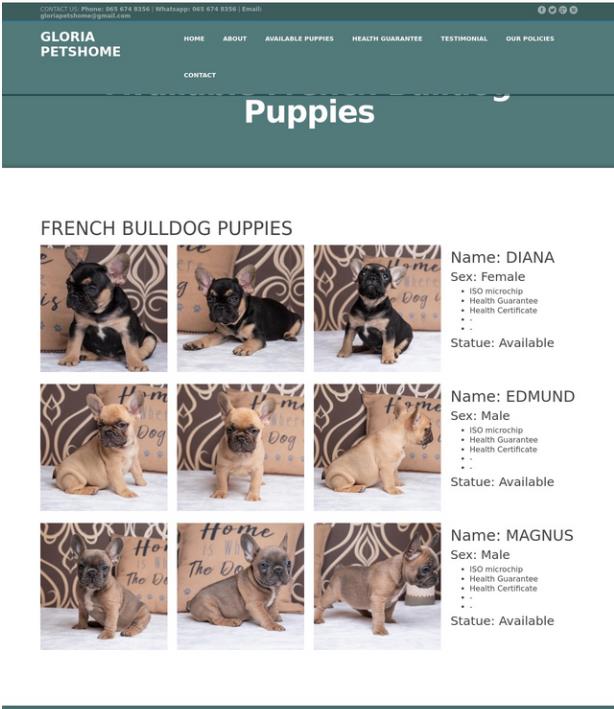

Let’s have a look at what to gloriapetshome.com is advertising:

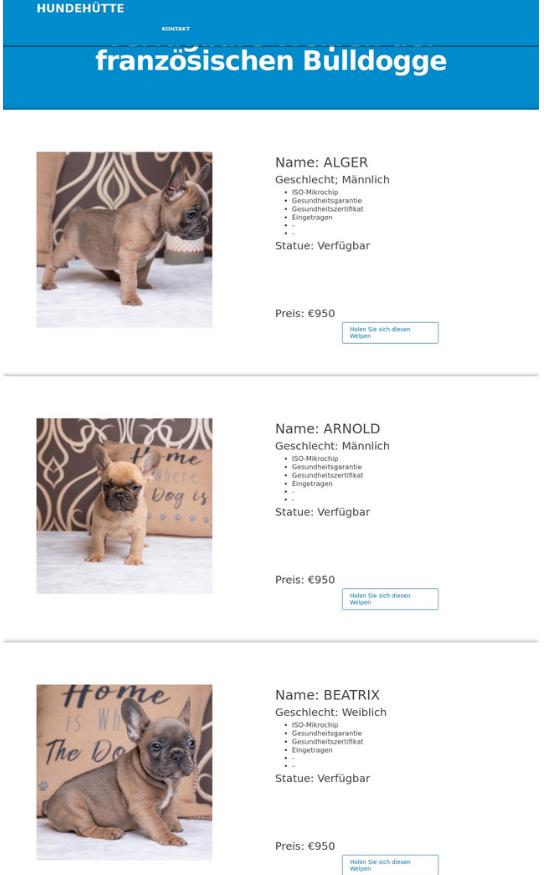

Now, imagine these same puppies being sold in Germany as well. Yet this is exactly what is happening in the case of domain kiarahundehutte.com.

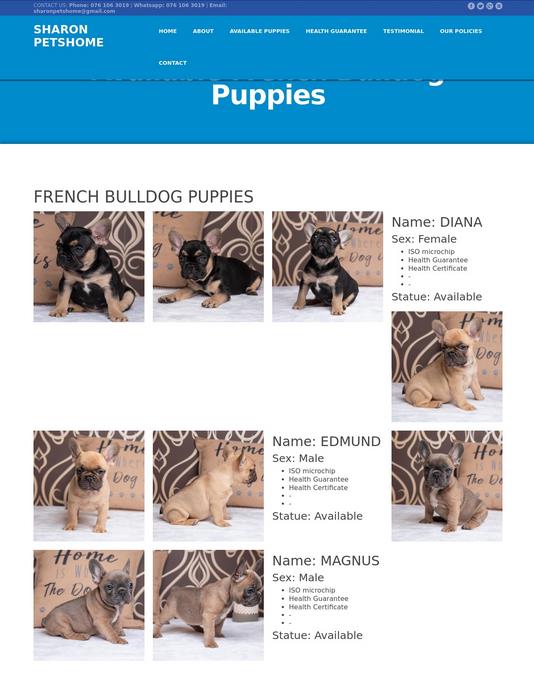

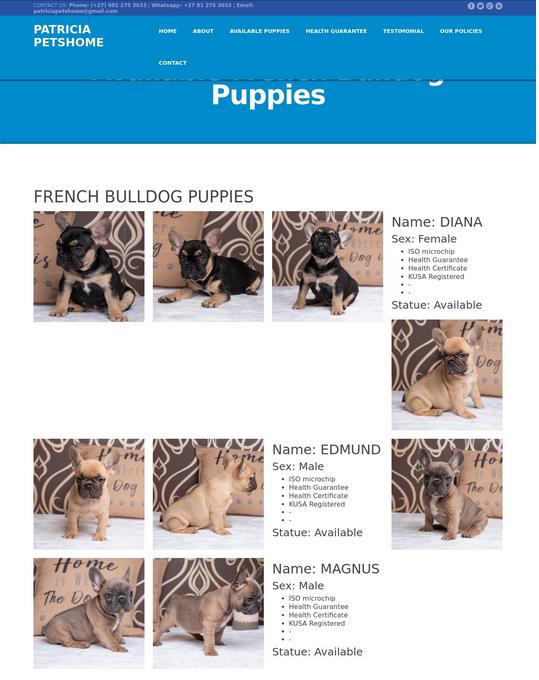

Its no surprise to see that Namecheap is also the sponsoring registrar, nor that their WhoisGuard is used to protect the identity of the criminal. Nor is it surprising to find that this is not the first time these images have been used for scam websites with victims. Enter patriciapetshome.com and sharonpetshome.com, also sponsored via Namecheap, using their WhoisGuard proxy.

Once again victims are piling up with no ability to check. Restitution is near impossible and each incident leads to privacy loss. Typically each website will have many victims leading to not only financial loss and money laundering, but also a loss of privacy. The effect is magnifying in nature.

However, Namecheap insists on a US court order to reveal the garbage they hide behind their proxies. Yes, we’ll get to the garbage part in a bit. Its not only Tucows and EPAG playing these games.

A while back, we saw a spate of Facebook spoofs where Facebook users were lured to websites claiming to be Facebook’s. Many victims fell for it. These websites were operated from Nigeria and South Africa. Facebook took action in an attempt at defending their users. It resulted in an ongoing court case. Namecheap claimed to be champions of privacy, defending their users:

https://www.namecheap.com/blog/the-secret-fight-for-your-personal-information/

The reality of who and what they are defending, is a bit more perverse:

https://securityboulevard.com/2019/01/facebook-lotteries-to-avoid-with-help-from-aa419/

https://about.fb.com/news/2020/03/domain-name-lawsuit/

Love or hate Facebook, but here they stood up for each and every consumer. We ourselves have recorded how ordinary real pet sellers were spoofed, had their website stolen with Namecheap defending the criminals despite clear evidence of fraud. Its against this background that we previously warned what the GDPR might be perverted to and that has since come true.

To dig a bit deeper into why Namecheap is a criminal’s choice sponsor, let’s have a look at a lovely parrot selling website called Siva Kumar’s Aviary hosted on domain affablebirds.com.

This domain is registered with Namecheap and protected by their Whoisguard proxy. Looking a bit further, we find a second website called Parrot Glory – Aviary hosted on domain name parrotglory.us.

In this case, the domain uses the .US top level domain. The United States wisely decided they will not allow proxies or hidden details in their domains. This allows us to see what passes for acceptable domain registrations at Namecheap; its garbage!

Registrant Name: sepe nipa

Registrant Organization:

Registrant Street: hsroyallogistics

Registrant Street:

Registrant Street:

Registrant City: hsroyallogistics.com

Registrant State/Province: ON

Registrant Postal Code: A1A 1A1

Registrant Country: CA

Registrant Phone: +1.8008008000

Registrant Phone Ext:

Registrant Fax:

Registrant Fax Ext:

Registrant Email: affablebirds@gmail.com

Registrant Application Purpose: P1

Registrant Nexus Category: C11

As before, despite there being policies to ensure domain registration accuracy, being one of the large registrar entitles you to consider these optional and allow your precious clients to ignore them, to defraud consumers. We could say Namecheap might not have spotted this?

Not so. We find affablebirds@gmail.com was also used to host a third website with the same content, Siva Kumar’s Aviary in domain sivakumarbirds.us, which was suspended.

We can see what it looked like, thanks to Petscams.com at https://petscams.com/puppy-scammer-list/sivakumarbirds-us/, also that’s it phone number was +12563689511. This is the same phone number we find on affablebirds.com.

As such its clear Namecheap had the opportunity to do the right thing, investigated, but clearly did not protect the consumer interest, only that of their good paying fraudster client.

It needs to be clearly understood, the commonality in all these discussions, even at ICANN, is what does consumer interest mean? Many registrars considers it to be their paying clients, not the internet user. If their user does something wrong, they will defend him. Do not threaten that which produces the riches. It does not matter if that precious client is paying with stolen money obtained from fraud and misery.

At this stage we need to have a look at what ICANN’s Government Advisory Council (GAC) said about domain abuse in its 2013 Beijing GAC Communiqué, even though referring to a new set of top level domains and referring to registries:

Making and Handling Complaints – Registry operators will ensure that there is a mechanism for making complaints to the registry operator that the WHOIS information is inaccurate or that the domain name registration is being used to facilitate or promote malware, operation of botnets, phishing, piracy, trademark or copyright infringement, fraudulent or deceptive practices, counterfeiting or otherwise engaging in activity contrary to applicable law.

https://www.icann.org/en/system/files/correspondence/gac-to-board-11apr13-en.pdf

This statement makes extremely clear what is considered domain abuse.

In 2019 in its GAC Statement on DNS Abuse we find this:

If the public is to trust and rely upon the Internet for communications and transactions, those tasked with administering the DNS infrastructure must take steps to ensure that this public resource is safe and secure. Recent privacy laws, including the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, have limited the public availability of information about the owners of domain names, creating challenges for law enforcement and cyber-security professionals tasked with combatting threats to the safety and security of the Internet

https://gac.icann.org/file-asset/public/gac-statement-dns-abuse-final-18sep19.pdf

Whereas we expect law enforcement to investigate if a consumer is defrauded, this statement hints at the frustration law enforcement encounters now with the GDPR being implemented in WHOIS. This statement also makes it clear that safety and security is being impacted. This is having an impact equally on consumers, companies and even government.

We also find a re-hash of what is considered DNS abuse.

Noting that ICANN community findings demonstrated that “consensus exists on what constitutes DNS Security Abuse, or DNS Security Abuse of DNS infrastructure,” the CCT Review Team referred to DNS Abuse as “intentionally deceptive, conniving, or unsolicited activities that actively make use of the DNS and/or the procedures used to register domain names.”14 The CCT Report used the term “DNS Security Abuse” to refer to more technical forms of malicious activity, such as malware, phishing, and botnets, as well as spam when used as a delivery method for these forms of abuse.

These definitions are consistent with ICANN standard contracts for registries and registrars. ICANN’s standard Registry Agreement required new gTLD registry operators to include provisions in their Registry-Registrar Agreements (RRA) that prohibited registrants from:

distributing malware, abusively operating botnets, phishing, piracy, trademark or copyright infringement, fraudulent or deceptive practices, counterfeiting or otherwise engaging in activity contrary to applicable law, and providing (consistent with applicable law and any related procedures) consequences for such activities including suspension of the domain name.

Despite this apparent consensus, certain registrars and registries decided to rather define what limited scope of maliciousness they will look at. This is then also published at http://dnsabuseframework.org/ and called the DNS Abuse Framework. In the link found on this page, we essentially find five types of activities these registrars and registries consider abuse:

Malware is malicious software, installed on a device without the user’s consent, which disrupts the device’s operations, gathers sensitive information, and/or gains access to private computer systems. Malware includes viruses, spyware, ransomware, and other unwanted software.

http://dnsabuseframework.org/media/files/2020-05-29_DNSAbuseFramework.pdf

Botnets are collections of Internet-connected computers that have been infected with malware and commanded to perform activities under the control of a remote administrator.

Phishing occurs when an attacker tricks a victim into revealing sensitive personal, corporate, or financial information (e.g. account numbers, login IDs, passwords), whether through sending fraudulent or ‘look-alike’ emails, or luring end users to copycat websites. Some phishing campaigns aim to persuade the user to install software, which is in fact malware.

Pharming is the redirection of unknowing users to fraudulent sites or services, typically through DNS hijacking or poisoning. DNS hijacking occurs when attackers use malware to redirect victims to [the attacker’s] site instead of the one initially requested. DNS poisoning causes a DNS server [or resolver] to respond with a false IP address bearing malicious code. Phishing differs from pharming in that the latter involves modifying DNS entries, while the former tricks users into entering personal information.

Spam is unsolicited bulk email, where the recipient has not granted permission for the message to be sent, and where the message was sent as part of a larger collection of messages, all having substantively identical content.

The various forms of Advance Fee Fraud do not make the grade. This entitles registrars and registries to turn a blind eye to two of the biggest cyber threats. It also shows a disconnect with the real cyber threat landscape on the Internet the consumer has to use.

West African (419) fraud and Business Email Compromise (BEC) goes hand in hand. The one is the mule recruiting ground which later turns inspecting innocent victims into money launderers in BEC. This has proven to be the biggest source of losses the past few years. Reports of BEC are trivially easy to find, yet very little is said about the 419 victim grooming process. Yet its this exact fight Artists Against 419 has been fighting since 2003.

It took the CovID pandemic to wake the world up to the existence of Non-Delivery Fraud. Working with a partner group, ScamSurvivors, we hijacked the resources of the anti-BEC community (with permission) to bring the incestuous nature of this type of fraud to the attention of the regulators and law enforcement. Interpol confirmed what we we seeing. As communities were being deprived of live saving PPE, we were reporting money laundering account after money laundering account. We were vindicated, having felt like Chicken Little since 2007, shouting at the world to wake up. In the meantime the registrar community had defined what CovID fraud would look like in DNS abuse, domain names with masks or covid. This cognitive bias served criminals well, not bound by any law or per-conceived misconception. It was neglected DNS abuse and a registrar unwillingness to understand that puppy scammers were scamming with more than just pets. It was also then gratefully we saw Interpol put out a Purple Notice on this fraud type. Ironically the first CovID fraud report linked to a syndicate in South Africa.

The DNS abuse framework does not address BEC. It does not know or care what a romance scam website looks like, what a fake bank looks like. That is unless it spoofs a real bank. In the latter case registrars and even some UDRP arbitrators will call it a phish in their ignorance. In turn this will lead to incorrect mitigation and further disinformation. This ignorance will also ignore a fake engineering company domain that will yield the next batch of money mules for BEC. Thankfully we had an opportunity to illustrate this type of DNS Abuse to the Edmonton Police when they had such a victim. The “nest” of connected malicious domains predicted an IRS spoof, not to steal personal details, but as a tool of persuasion. This also later came true and mitigation had to be done.

These registrars and registries are quick to pass the buck to law enforcement. Yet this approach ignore the fact that many cases opened by victims will gather dust. To understand why, we need to consider law enforcement is has finite resources. Jurisdiction issues also hamper law enforcement. Politics also plays a role. The consumer interest comes last.

The GDPR in domain WHOIS also disavows consumer protection. It effectively means something might be done after a consumer has been defrauded. Then we have to trust a registrar to ensure the party undetermined third party rights, has not set up more criminal infrastructure. The Namecheap parrot scam shows how well this is done. We need to ask if this is in effect protection? The damage is already done. Any costs is solely for the account of those harmed.

Let’s make this very clear. Domain privacy can and does undermine security. In turn this leads to the deprivation of both consumer security and privacy. Unlike big company, the most vulnerable are then left stranded to their own devices and turned into criminals’ prey by the GDPR and privacy in domain registrations.

Yet many registrars and registries refuse to acknowledge the reality that they have created for consumers, where even the ability to do the most basic of checks has been removed from the consumer, where they are now being called stupid in victim blaming exercises after being scammed by Redacted for Privacy.

Having exposed how privacy is being perverted, how criminals are now shielded with superior rights to victims, imagine a common consumer with limited financial resources being the victim of fraud and identity theft. We leave you with some excellent insights from Gary Warner: Why Do We Call it Cyber CRIME?